Hard times for regional airlines but not without opportunities

News broke this week that Cathay Pacific will be closing its subsidiary Cathay Dragon and cutting 8,500 jobs. It has been a hard 14 months for the airline. The first two weeks of August 2019 saw the highest ever scheduled airline capacity at Hong Kong Airport, having grown steadily over many years, but since then flights have plummeted, initially due to the unrest in the city and then due to the pandemic and travel restrictions.

While the intention is to continue operating many of the Cathay Dragon routes under the Cathay Pacific or Hong Kong Express brands, a move which requires regulatory approval, the loss of Cathay Dragon highlights the difficult trading conditions for many of the world’s regional airlines.

Generally, regional airlines fall into one of three types:

- They may be a subsidiary to a larger network carrier, providing feed traffic to hub airports or providing an alternative brand for the low yield point-to-point traffic that the major carrier doesn’t want to dilute its main offering.

- They may be a third-party operation, providing regional and commuter services on a contractual basis for a major network carrier.

- They may be an independent entity and entirely free to determine their own market position and network strategy.

Regionals need to right size their fleet

Cathay Dragon falls in to the first type, the subsidiary. This type of regional airline serves the purposes of the owner and the strategy will always ultimately be determined by the strategy of the group.

Earlier this year Austral Lineas Aéreas met a similar fate as Cathay Dragon, with the parent company Aerolineas Argentinas folding operations into the main carrier brand and losing the regional brand as a means of cutting costs due to the pandemic.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Back in 2007 Malaysian Airlines launched Firefly as a full-service regional subsidiary, serving the leisure market and connecting secondary cities in the region. While both airlines have responded to weak demand by reducing capacity, Malaysia Airlines has reduced the number of seats it flies by almost 60% in the period January to October this year compared to the same period in 2019. However, the same figure for Firefly is only 27%. While generally the impact of COVID-19 has been less on domestic markets, 20% of Firefly capacity in 2019 was international and 10% of its capacity has been on international routes this year too.

Possibly the key difference between Firefly and the likes of Cathay Dragon and Austral is in the size of aircraft being operated. While the Cathay Dragon fleet consisted of A320/321 aircraft along with A330s, making for an average of 233 seats per aircraft, the Firefly fleet currently consists of 12 ATR72 turboprops. Now more than ever, when passenger demand is likely to be focussed on short and regional haul routes, it is important to have the right sized aircraft for the markets and for some time that may be smaller aircraft than has been the case for some time. The smaller aircraft size typically used by regional airlines may well be an advantage in the current climate. Having said that, Firefly has indicated this month that it may start flying jet aircraft as soon as the first quarter of 2021, deploying 737-800 aircraft currently held by Malaysia Airlines.

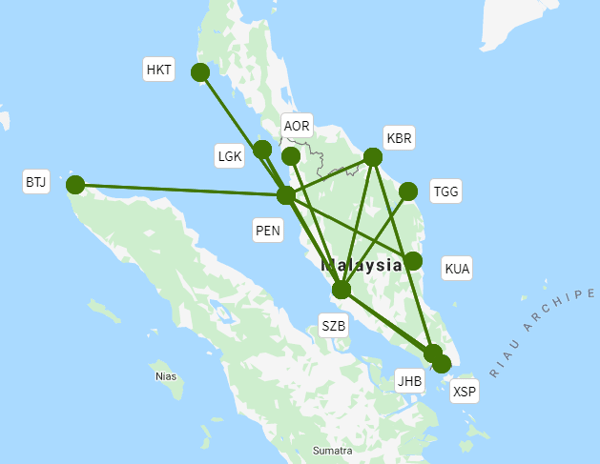

Firefly Route Network October 2020

Source: OAG Anlayser

Source: OAG Anlayser

Vulnerability when it’s not your hub?

As is the case with Austral and Cathay Dragon, when a parent airline decides it is time to close the subsidiary brand, it is still possible that some of the routes will be retained, just with a different operator. However, for the regional airlines which operate as third-party suppliers and wet lease operators, the decision to cease the relationship can be even more painful. In August 2019 Delta Air Lines decided to reduce the number of regional carriers flying under the Delta Connection brand and ended its agreement with Compass Airlines. With the pandemic compounding its problems, United Airlines also reduced the services required, and the airline ceased trading in April this year.

For any regional airline which is based around the hub airport of one or more major carriers, there is a risk that the hub will not be needed in the same way, although there is an argument that the smaller aircraft size typically used makes them a more efficient option in current times. The pandemic has brought to life another risk, the one that passengers would prefer to travel directly and bypass hub airports altogether.

At one stage Breeze, the new airline being launched by David Neeleman, the co-founder of JetBlue and other US low cost airlines, had Compass in its sights for acquisition, but changed its mind. Even before the pandemic, Breeze had identified an opportunity for a new airline serving secondary cities with point-to-point operations which they considered to be underserved. Breeze is currently due to start flying in March 2021 and has orders for 60 new A220-300 aircraft due to arrive later in the year which will provide lower operating costs as well as scope for a premium cabin, something the Compass E175’s would not.

Is independence the answer?

Given the problems that can arise for regional airlines that are dependent on other larger airlines, either through ownership structures of contractual agreements, is it any easier for independent regional airlines? There are certainly no shortage of airline start-ups trying to get off the ground.

European regional airlines such as Widerøe and Loganair, while still seeing demand fall year-over-year have fared better than many larger airlines. Widerøe is currently operating 22% less capacity than a year ago and Loganair 39% less. Widerøe has a fleet of predominantly Dash-8’s and a handful of ERJ190s, while Loganair operates a mixed fleet of Saab 340s, EMB145s, ATR 42s, ATR72s and some other aircraft. Of course, the mix of routes flown which includes Public Service Obligation (PSO) routes helps.

Rex – or Regional Express Services – the largest Australian regional airline outside of the Qantas Group, has seen capacity fall by more than Loganair or Widerøe but is still able to see the opportunities available. Like Firefly, the airline has only operated turboprop aircraft until now – it has a fleet of 57 Saab 340s – but has been eyeing up ex Virgin Atlantic 737-800s which may be going cheap. The airline is due to take delivery of 6 of these aircraft within a month.

Many of these smaller independent airlines have survived, even thrived, by creating a balanced portfolio which might include a mix of PSO operations, ACMI/wet lease services to larger carriers to feed a hub aircraft, charter operations for special events and sports teams, as well as some cargo and logistics traffic. It is this flexibility to respond to the market which is one of their strengths.

Recognising the opportunity

Perhaps the answer, as always, is in making sure that there is a clear market opportunity for the service being offered and reaching for other opportunities as they come along. It’s clear that some regional airlines may be benefiting from their use of smaller aircraft, but equally that they may be able to expand their fleet earlier than originally planned given the availability of excess aircraft. In more normal times different ownership patterns may have mattered less than understanding the strategic purpose and market fit for the airline but the pandemic has shown that in a sharp downturn, subsidiaries and suppliers may be perceived as expendable and the first to go when costs need cutting. Independent regional airlines may be the ones to face more challenges usually when it comes to financing their ambitions but just now, they may be having an easier time.

.jpg)

.png)