As aviation starts what increasingly looks like a long and slow recovery towards filling seats, comprehensive flight route networks and confident travelers, the past week has seen numerous news features and articles about the creation of bubbles. Certainly, the notion of “clean” bubbles in which travel is relatively unrestricted and low risk are an attractive alternative for the industry compared to 14-day quarantining of international arrivals which all but squashes the most essential international travel.

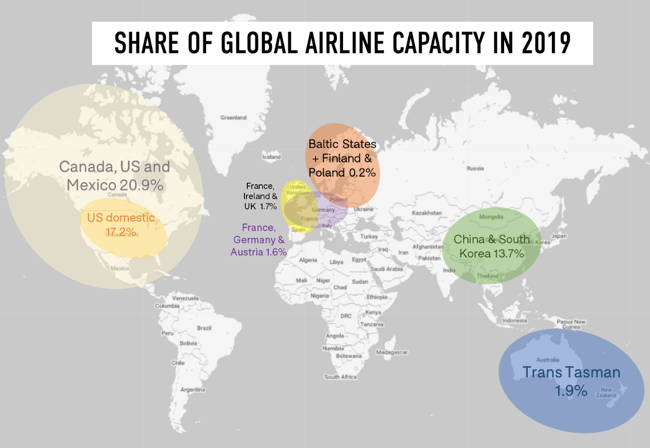

A number of travel bubbles have been announced, or at least discussed. There’s the Baltic States of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, which are now discussing adding Finland and Poland. The inclusion of Finland highlights that these travel bubbles, of course, can include countries that don’t share a common border and can be air bridges rather than travel bubbles. There’s another possible travel bubble emerging between France, Germany, and Austria. The UK government announcement of quarantine exceptions for France* and Ireland immediately gave rise to the notion of an Ireland/France/UK bubble, even if that might sit uncomfortably with the EU.

Across the pond travel restrictions between the US and Canada may end on May 21st creating a North American bubble - or they may not. Another travel corridor of less restricted flying is between China and South Korea which has introduced fast-track flying for business travelers. Then there is the Trans-Tasman bubble, allowing travel between Australia and New Zealand.

The value of these travel bubbles, or corridors or air bridges, whatever you choose to call them, is that they provide a hesitant step toward recovery. They give a sense that things are getting back to normal; that people can fly again. What they don’t do is make much difference to the actual amount of flying that could be happening.

Take the Trans-Tasman bubble, for instance. In 2019, capacity within or between Australia and New Zealand made up just 1.9% of all global airline capacity, and the international element of that was less than 10%. The Baltic bubble accounted for only 0.2%.

The biggest travel markets are all domestic. The US and China (or China and the US, in that order, as of last week) dominate. So, a bubble made up of Canada, Mexico and the US would still mostly comprise US domestic capacity, with a large element of Canadian domestic and Mexican domestic capacity too. Flights in any bubble including China is still mainly about Chinese domestic travel.

The Economist this week suggested much larger travel bubbles, based on groups of countries that met certain criteria, could make a significant difference. It looked at groups based on how many new cases of covid-19 there had been in the past week relative to the size of the general population. They recognised, however, that even with some systematic agreement such as this between countries which would enable the opening up air travel on a bilateral basis, a lack of trust would probably still hamper efforts.

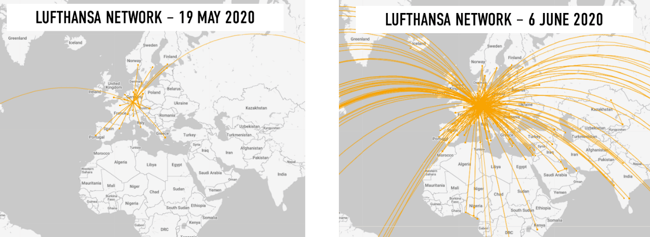

In the meantime, while governments make noises which signal a loosening of restrictions, airlines appear to be planning in a parallel universe. Take the example of Lufthansa.

|

LUFTHANSA ROUTE NETWORK |

||

|

|

19 May 2020 |

16 June 2020 |

|

Countries |

18 |

74 |

|

Routes |

28 |

263 |

|

Flights |

94 |

1,609 |

|

Seats |

12,670 |

271,555 |

In the space of 4 weeks, between 19 May 2020 and 16 June 2020, the carrier schedule will move from a network that serves 18 countries, to one that has flights to 74. The number of flight routes being flown will expand from 28 to 263, Daily flights will increase by a factor of 17 while seats will grow by a factor of 21.

Of course, along with adding flights back into their schedules, we may also see a large number of cancellations. If national restrictions are still in place in 4 weeks’ time who will be traveling and even if restrictions are lifted it is not yet a given that demand will follow supply.

*Accurate at time of publishing

.jpg)

.png)