MIDDLE EAST AVIATION

Transformation, Growth and Future Challenges

Discover OAG's latest in-depth report focused on the Middle East aviation market

- Introduction

- A Constantly Climbing Market

- Striving For Profitability

- Disruptive Market Forces

- New Airlines, Aircraft Orders & Resources (Eventually)

- Balancing Product Mix and Market Creation?

- Help Yourself to My Market – Not!

- Balancing Ambition with Reality

Continue reading to discover the full report and data, or click here to download a copy.

Introduction

Forty years ago, most international airlines viewed the major Middle East markets as a purely technical stop on their way from Europe to South East Asia, providing cheap fuel in the early hours of the morning as their aircraft crossed paths somewhere over the Indian Ocean at 35,000 feet.

A few large airlines, such as Saudia and Gulf Air, offered low frequency services across the region, catering exclusively to the very rich with luxury first-class treatment available on every flight. Fast forward to 2024 and the Middle East is now one of the fastest growing markets in the world, with leading global airlines competing to operate the most comprehensive networks in the world with the highest levels of service possible.

The transformation can only be described as incredible, visionary in thought, near perfect in delivery, and resulting in the region becoming the center of the aviation industry, linking nearly every major city in the world to at least one of the region’s major hubs. Four decades ago, many would not have believed the dream was possible - today that dream is reality, surpassing even the most optimistic expectations. However, aviation never stands still.

Pause for breath in the aviation industry and the vapor trails of progress will pass by. Many airlines, former CEOs, shareholders and passengers can confirm this reality as the industry constantly evolves. New competitors appear from nowhere, emerging markets spring up in response to changing geopolitical circumstances, and entrepreneurs who’ve smelt JA1 Kerosene chase their dreams of launching an airline start up; taking millions of dollars and turning them into mere hundreds overnight!

In the aviation industry, change is constant; innovation is a daily occurrence and boundaries are forever being pushed. This contributes to an exciting industry that accounts for a GDP of US$ 3.5 trillion, making it equivalent to the world’s 17th largest country, and that’s before we think about the next decade of change in the aviation sector.

In this report, we explore how the Middle East has been so successful in its growth over the last forty years, highlighting some incredible statistics and recognizing that history counts for nothing. We also look ahead to the next decade, which promises to be the most exciting and potentially disruptive period of change. So, seat belts on and let’s take off!

A Constantly Climbing Market

Whilst we all hear regular stories about new aircraft orders in the region, and new flight routes and airlines being opened, we probably do not quite realize the rate of growth in the region since the turn of the century. However, the following two data points clearly highlight just how rapid that growth has been.

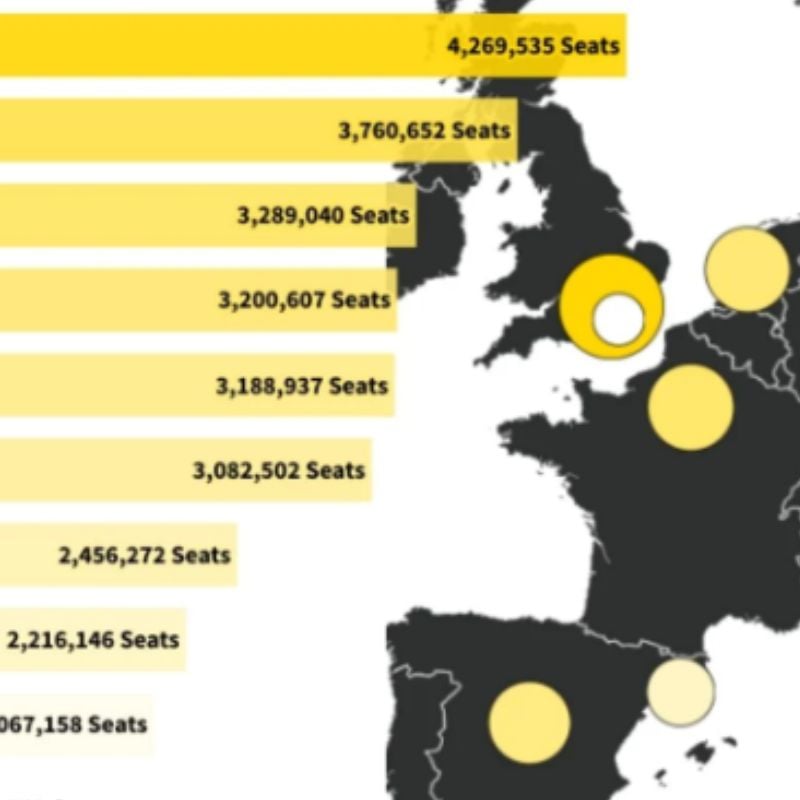

- In 2000, the Middle East ranked globally as the seventh largest region with 70 million seats per annum. This year expectations are for 257 million seats, in touching distance of South Asia which is dominated by the Indian domestic market.

- Since 2000, the Annual Average Growth Rate (AAGR) has been 6.8%, which is twice the global rate. And if measuring by Available Seat Kilometers (ASKs) by virtue of the typically longer sector lengths and wide-bodied capacity operated from the region, that AAGR rate increases to just over 9%. Of course, hidden in that regional average are a series of winners and losers.

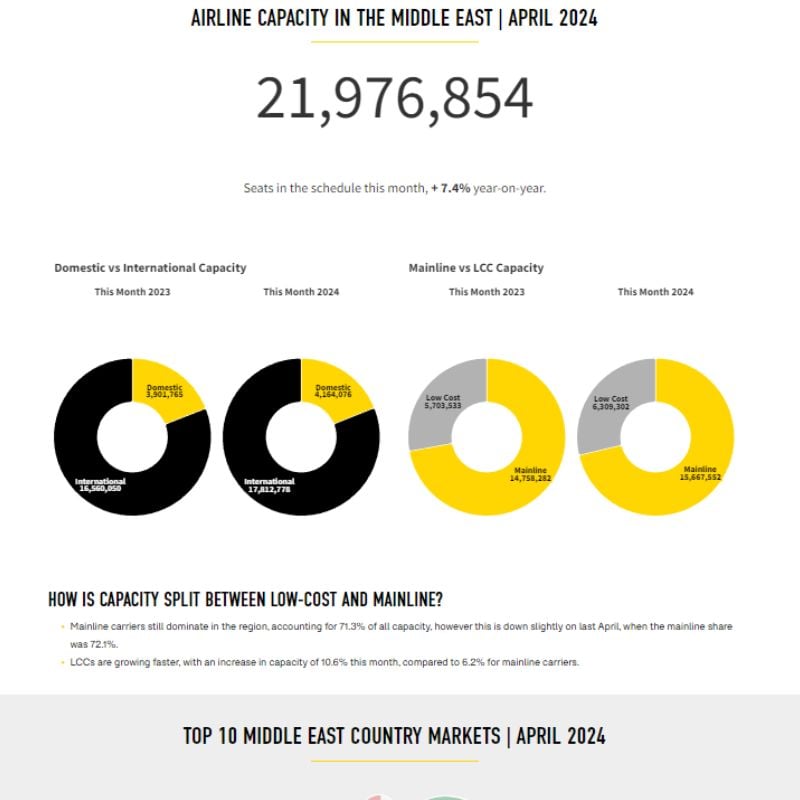

Whilst two markets dominate - the UAE and Saudi Arabia - their market structures are very different. In Saudi Arabia, 45% (33.6 million) of seats are operated on domestic services, whereas the UAE market is 100% international capacity. Collectively these two country markets account for 61% of all airline capacity in the region, and when Qatar is added in third place the top three are responsible for nearly three-quarters of all capacity in the region. Unsurprisingly, given the size of the top three country markets and their investment in the aviation sector, the AAGR rates are all higher than the regional average; Qatar leads with a very strong 12.5%, implying a potential doubling in capacity every six years. The sustainability of such growth going further forward is an interesting aspect to consider given how the market is developing.

Countries that have been growing at above market averages have also faced challenges. In some cases, this is due to geopolitical issues affecting demand, in others economic and market growth has just not been as strong, such as Kuwait and Bahrain where - in the face of increasing competition - local airlines have perhaps struggled to establish long-term strategies.

In line with market growth, the number of airlines operating within the Middle East has increased since the turn of the century. In 2000, 135 scheduled airlines operated services, that subsequently peaked in 2023 with 213 carriers operating. The balance between locally based and non-domiciled regional airlines shows that the number of locally based carriers has doubled in the last twenty years, to 36 in 2023 compared to the 177 overseas based carriers. The current ratio of 4.7:1 compares favorably to the 2000 ratio of 7.4:1; with more locally based airlines operating, more direct employment and income for the local economy is created.

Since 2010, the number of airlines operating in both segments appears to have stabilized, averaging around 160 non-domiciled carriers and around 38 locally based airlines. And although new destinations are continually added, these are typically from the local airlines rather than new overseas carriers entering the market.

Looking as far back as 2000, numerous locally based airlines have been in operation throughout the first quarter of the century, including Saudia, Emirates and Oman Air. Perhaps surprisingly, Etihad was established in 2003 and FlyDubai in 2009, yet both carriers now rank in the top five airlines based on capacity. Amongst the non-domiciled carriers plenty have operated continually through the century, with network carriers such as Turkish Airlines, Ethiopian Airlines and KLM ever present. Whilst constant migrant worker traffic has allowed airlines such as PIA, Air India and Biman Bangladesh Airlines to grow their business.

Unsurprisingly, airline and capacity growth has resulted in the number of airport pairs increasing since 2000, as the table below outlines, with both locally based and non-domiciled carriers adding new airports on a regular basis. There are now nearly twice as many airports served from the Middle East, although the 2020 high water mark has yet to be reached post-pandemic. Competition between both local and non-domiciled airlines exists on nearly 400 airport pairs (20%), which certainly keeps the market fares competitive, especially when the competition is frequently between legacy and low-cost airlines.

Amongst the major local Middle East airlines, the number of airport pairs served over the years shows a mixed picture, whilst also reflecting the changing mix of carriers in the region and product segmentation. Saudia operates the most airport pairs, with the only domestic market of note in the region, although in recent years some route handovers to FlyNas have seen their total count reduce from a peak of 283 in 2015 to 205 in 2024. This may well change further given the wider national strategy now being adopted in the Kingdom.

Interestingly, Qatar Airways serves more airport pairs than Emirates, although the combined Emirates and FlyDubai network stands at around 251, with just 32 airport pairs served by both airlines, including points such as Riyadh, Karachi and Male. Both Emirates and Qatar operate an average of two flights a day on each airport pair. For comparison, after Gulf Air’s network shrank as changes in ownership structure reduced their focus to purely a Bahrain base, the airline maintains an average of two flights per day to each airport pair served, highlighting that for all locally based airlines frequency of service is important.

Striving For Profitability

Despite the near constant growth, profitability has not always been possible in such a competitive market, especially amongst the smaller locally based airlines that struggle for market share and where their product offering doesn’t quite match the ever-growing carriers such as Emirates and Qatar Airways.

There is certainly a “bigger is better” feel to the Middle East market with the larger network carriers posting exceptional levels of profitability in 2023. Emirates’ latest six-month results reported a US$ 2.7 billion profit and Qatar Airways (for the same period) a US$1.0 billion profit. With both carriers confident of stronger second halves to the year we can expect record breaking announcements in the next few weeks from those airlines. Unfortunately for the smaller airlines in the region, some of whom are obligated to operate routes that perhaps fulfil more of a social rather than commercial requirement, profitability is more of a challenge.

Oman Air has struggled with profitability - although the airline reduced its losses by 25% in 2023, it has yet to make a profit despite an expensive product offering, expansive network, and previously ambitious plans that are now once again being reviewed. In 2016, the airline paid a record US$75 million to KLM/Air France for a pair of London Heathrow slots, and it remains difficult to see how that price has ever been recovered from the wider network benefit. In today’s market such prices are unlikely to ever be repeated.

Similarly, Saudia - the region’s largest airline - is hopeful of returning to profitability by the end of this year, despite a slowdown in market growth coinciding with expansion into new destinations in the last twelve months. Saudia are now likely to be acquired by the Saudi PIF fund as part of their wider investments across the Vision 2030 project, which may or may not take the issue of profitability away for a while as the airline begins to turn its attention towards a Jeddah base and development of religious traffic to the country.

Like other major regional markets around the world, it’s clear that whilst the dominant carriers in each market can generally be profitable and provide returns to shareholders the Tier Two and smaller carriers are constantly struggling to break even. In North America, United, Delta Air Lines and Southwest consistently deliver profitability. In Europe, Ryanair, IAG, Air France/KLM and Lufthansa deliver shareholder value over an economic cycle. However, for many carriers profitability appears almost impossible and survival is a daily success story.

For many airlines operating in the Middle East, with profit margins right on or indeed firmly below the line, a sudden and significant change in the market could be extremely disruptive and any such change could have many airline CEOs ducking for cover. However, that is exactly what is likely to happen in the next five years as Saudi Arabia ramps up its investment around the Vision 2030 project and the impact is going to be dramatic for all - or is it?

Disruptive Market Forces

The aviation industry has always been challenged by new and occasionally disruptive forces. Geopolitical events, pandemics and environmental events have all impacted capacity and demand around the world. In many cases such “shock events” result in short-term changes and then the market returns to its normal capacity and demand profiles within twelve months. The Covid-19 pandemic has broken all records with a near four-year recovery in most markets, but happily that is nearly over in every market. With the pandemic now firmly behind us, attention turns to the next big development that may just carry a disruptive element to the Middle East aviation market: Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030.

Vision 2030 has taken years in the planning and represents one of the most fascinating and expensive economic transformation projects in the world. The plan to turn an oil-dependent economy into a major service and tourism-based economy is visionary, exciting and hugely expensive, capturing the attention of airline and airport CEOs throughout the region. Investing over 12.4 trillion Saudi Riyals (approx. US$3.3 trillion) the total project has three targets: to create an ambitious, vibrant, thriving society that through a series of transformational programs places Saudi Arabia as the key commercial and cultural center in the Middle East. It aims to eclipse anything yet seen in the United Arab Emirates, or more recently Qatar. In Saudi Arabia, such ambition cannot be achieved without a dramatic change in the aviation market. Plans are already well developed to achieve those objectives with alignment to the larger infrastructure investment in major cities, in which projects at airports are just one element.

By 2030 the Vision 2030 plan calls for tourism to account for over 10% of GDP; generating at least one million additional jobs as GIGA projects (such as NEOM, Amala and the Red Sea Project) attract tourists from around the world seeking a combination of cultural and beach holidays. An additional 150,000 hotel rooms will become available in the next few years, including seven-star luxury accommodation investments in locations such as Al Ula and the Red Sea Resorts. Hopes are for over half a million hotel rooms to be available per night by 2030.

Facilitating such growth is challenging; significant infrastructure investment, skills training, easing of visa requirements, and some very expensive branding and destination awareness campaigns targeted at high-worth travelers worldwide are only part of it. But perhaps the largest part of the story is around the ambition for increased visitors to the Kingdom, and with that ambition both the direct impact on the local aviation market and the subsequent “ripple” effect in other markets across the Middle East.

Vision 2030 has a target to reach 300 million air passengers by 2030, 100 million of whom will be tourists (however that classification is determined). This is an extremely ambitious target considering that the current estimated passengers (to/from Saudi Arabia) in 2023 is 107 million, as the table below shows.

Having access to a domestic market of nearly 43 million passengers annually provides a solid platform for the total market. However, achieving that target will require levels of international capacity growth never seen in any market. To achieve the required volumes, demand will need to increase by over 20% per annum through to 2030, a level of growth three times higher than the average since 2010 through 2019 and the pre-pandemic levels. Such a sustained rate of growth has never been achieved in any major country market. And whilst the target is visionary, achieving such a number is becoming increasingly challenging as the aviation sector faces a series of supply challenges.

Naturally, there is huge confidence within the local market that Saudi Arabia will reach its targets under Vision 2030 and indeed, realizing even half of their aspirations would be a remarkable achievement. So, what are the key factors that will determine how close Saudi Arabia will get to a 300 million air passenger market by 2030?

New Airlines, Aircraft Orders & Resources (Eventually)

One of the fastest accelerators of growth is to launch a new airline alongside the existing locally based carriers. This leads to the launch of Riyadh Air and perhaps one or two other carriers that will finally be announced in the next few months.

Riyadh Air has a hugely ambitious plan to connect the capital city to over 100 international destinations, potentially creating around 200,000 jobs. They have also placed an order for 39 B787s with the first deliveries initially expected in 2025, although Boeing’s ongoing production issues may result in the initial timescales being delayed. Additionally, in November 2023, the airline’s CEO, Tony Douglas, was quoted as saying they were weeks away from announcing their narrow-bodied fleet order. However, weeks have now turned into months and the ongoing issues at Boeing (and to a lesser degree Airbus) appear to have disrupted this plan. Either with or without the narrow-bodied aircraft order, Riyadh Air are unlikely to be a significant capacity provider before the end of 2026 at the earliest, given the necessary ramp-up that any new airline encounters. As each month passes, their contribution towards that 300 million passenger target becomes ever more doubtful.

The launch of Riyadh Air allows Saudia to focus on Jeddah and the religious markets to the city, along with commercial demand. It also probably means that Saudia will have to give up some routes to Riyadh, and perhaps even slots at constrained airports such as London Heathrow. The revised focus also places more emphasis on Saudia to operate profitably with a much clearer focus and business strategy, including the utilization of the 39 B787s ordered in 2023. With an almost “guaranteed” religious market to cater to, strong domestic demand, and an established regional market, it should almost be impossible for Saudia to fail. However, only time will tell if they deliver on that clearer market position.

Alongside Saudia and Riyadh Air, other new airlines are under development in Saudi Arabia. Planning to launch later in 2024 are NEOM Air, who are promising levels of service in line with visions for the wider development of the area. NEOM Air currently has no IATA designation and even more importantly no aircraft ordered, or announcements of any network plan, all of which makes a 2024 start look doubtful. Of course, aircraft can be leased at short notice, but the ongoing delivery issues have resulted in airlines extending current leases. Plus, given the high-quality service that NEOM aim to deliver, retrofitting cabin interiors make that option seem unrealistic as well. Still wider supply chain issues have resulted in many of the original NEOM projects falling behind schedule, so perhaps a delay in the new airline is the least of the problems being faced.

Aircraft aside - and that is a major issue - a larger point is perhaps the availability of qualified staff to run the operational side of these enlarged airline operations. Whilst Riyadh Air aims to be digitally native, and NEOM Air hopes to operate “innovative aircraft”, attracting a pool of qualified pilots with experience may be challenging.

Before the pandemic, forecasts predicted a global pilot shortage reaching nearly 35,000 by the end of the decade. Post-pandemic, that shortage has become more severe. Despite efforts to refuel the labor pipeline, it is taking longer than anyone could have hoped. All of which means airlines in Saudi Arabia are probably going to have to pay above market rates for experienced flight crews. Despite the attractive tax-free benefits in Saudi Arabia, similar perks exist in other parts of the world. This all makes the “come and work for us” pitch challenging, leading to recruitment fairs around the world this year!

Balancing Product Mix and Market Creation?

Excluding the localized issues of aircraft availability, resources, and completion of masterplan projects on time, the key question remains: where will the 300 million passengers come from, and how sustainable will that demand be over time?

Stimulating local market demand is the most obvious source, although equally perhaps the hardest to create - especially at the required levels to achieve the publicly quoted targets. Market stimulation typically comes from a combination of low-cost airlines - of which there are many active in Saudi Arabia - and by providing accommodation options that provide high quality value for money, which might not align with the current product positioning of the luxury resorts that are under development. A quick search of accommodation at the Red Sea resort in October offers a 6-night package at the St Regis for £11,200, or the Six Senses Southern Dunes for £8,327; in comparison similar luxury accommodation in South East Asia is half the price, and even the Caribbean works out cheaper.

While the development of luxury accommodation may align with the aspirational goals of Vision 2030, it seems disconnected with the practicality of attracting visitors beyond the very wealthiest of travelers. Creating a market of 300 million passengers, 100 million of which are tourists, and introducing six-star accommodation products is unlikely to deliver the expected outcomes.

Help Yourself to My Market – Not!

The success of other locally based airlines has - at least initially - been established on attracting connecting traffic between various regions in the world. For Emirates, the initial foundations of their network were based around connecting traffic from Europe to the Indian Subcontinent and South East Asia, often attracting travelers with appealing stopover packages on the beaches of Dubai. More recently, the local market demand has matured to a point where it now accounts for just over half of all traffic, representing a mere 23 million connecting passengers annually for the airline.

In Doha, the proportions of connecting traffic are closer to 85% and on some routes even higher as Qatar Airways seek to match the network of their UAE-based competitors. While slightly beyond the Middle East region, the new Istanbul airport and growth strategies for Turkish Airlines, which already flies to more countries than any other airline globally, suggest that developing connecting traffic via Riyadh will require a very competitive product. This offering should combine low airfares, rapid connectivity, and attractive stop-over packages in Riyadh for interested travelers, despite the absence of a coastline that may deter some potential connecting passengers. And of course, it would be naïve to expect anything other than a competitive response from all the locally based airlines in the region, many of whom have significant aircraft orders of their own for the next few years, as the table below highlights.

Collectively, the ten largest airlines in the Middle East already have a combined order book of 795 aircraft to be delivered by the end of 2029; on a regional market basis it is one of the largest order books in existence. In their latest global market forecast, Airbus estimate that around 58% of all new aircraft deliveries will be for network expansion; apply that ratio to the 795 aircraft that these airlines have on order, assume an average capacity of 160 seats per aircraft and assume a low average utilization of four flights per day, and by 2029 an additional 107 million extra seats will be added to the market by those locally based airlines. Although around 16 million of those will be supplied by Saudi-based carriers, the degree of competition from competing airlines (with their own new capacity) will add a further degree of complexity to the market conditions, not just for Riyadh Air and Saudia, but for the ambition of Vision 2030.

Balancing Ambition with Reality

The need to adjust the dependency of Saudi Arabia away from an oil-based economy is a necessity. The focus on sectors such as travel, aviation/aerospace and the service sectors is a natural evolution for the economy. The aspirational nature of Vision 2030 is something that has captured the imagination of everyone, and certainly has architects desperately trying to out-design each other on a near daily basis. From a positional perspective, Saudi Arabia was always going to try and out-do its close neighbors, and the targets are certainly in keeping with that objective.

In summary, achieving those targets is already beginning to look in doubt. A difficult aircraft supply market, securing the required number of experienced operational staff – which is likely to prove expensive at the very least - and a lengthy list of competing airlines, that will not give away their existing business, easily makes delivery of the 300 million passengers by 2030 seemingly unattainable, even amongst the most optimistic.

However, if Vision 2030 only achieves half of its ambition by the end of this decade, an additional 100 million passengers passing through Saudi airports would still represent a remarkable success story for the Kingdom.

MORE RESOURCES FROM OAG

China Aviation market Data

The busiest airports, largest airlines, biggest cities for airline capacity and more

View Data

Middle East Aviation Market Data

This month's leading airlines, airports, and more in the Middle East market.

View Data

South East Asian Aviation Market Data

SE Asia's biggest country markets, airports, airlines and more are updated each month.

View Data

Aviation Market Analysis

Analysis of the latest data and developments in the aviation world.

Read Now

.jpg)

.png)